A very brief overview of Program Synthesis

Starting a couple of months ago, CIn-UFPE’s Software Engineering Laboratory started organizing seminars given by its members. The goal is to make laboratory members aware of work being conducted by other members. So far, I’ve greatly enjoyed these seminars. In one of them, I learned a bit about cloud computing and also about electronic government (which seems to be an area of research that sits between Computer Science and Political Science) from Prof. Vinicius Garcia. Last week we had one given by Prof. Alexandre Mota. One of the things I admire about Alexandre is that he is a hard core Formal Methods guy with a remarkable track record of collaboration with industry.

Alexandre’s talk started with an overview of formal methods. According to Alexandre, formal methods are a combination of notations, tools, and a semantics based on mathematics. Their use can help developers to ascertain that there is no ambiguity, imprecision, inconsistency, and (for some systems) incompleteness in a system specification. This is the good side of formal methods. The bad side is that, to get from a specification to a correct system, there is a myriad different paths and each one of them is tough to traverse. And this is assuming that a formal specification exists. Going from an informal specification to a formal one is a very difficult problem in and of itself. It requires a thorough validation and the assistance of specialists.

Alexandre also discussed the process of program refinement, going from a formal specification to executable code in a way that guarantees that the generated code satisfies the specification. According to him, there are two paths to go from formal specification to a correct system: (i) by data and operation refinement; and (ii) by refinement calculus (using a set of refinement rules). In the former approach, we’re transitioning from a specification S0 to a specification S1 and S1 is not determined by pre-established laws. One needs to propose and verify each refinement. It is possible to apply more broad-scoped transformations using this approach. In the latter, the transformations one can apply to the specification are constrained by the laws one is using. This is good because the proof obligations are relatively straightforward. The bad part is that it is more constraining and requires very experienced engineers. The “search” in refinement calculus may never end. Both approaches require searching for the specifications and for the theorems that must be proved. It is a search problem and leads us to the problem of program synthesis.

After presenting a (critical) view of formal methods, he narrowed down the scope of his talk, focusing more on the subject of program synthesis. The problem of program synthesis can be summarized as follows: Build a system that, given a specification and optionally a set of program fragments, produces as output a program that satisfies (refines?) the given specification and also includes the given program fragments. Program synthesis is a search problem because a large part of the work performed by a program synthesis system consists of searching through a space of candidate programs and checking whether they satisfy the specification. This problem is tough. In fact, part of it usually involves solving SAT, the most famous NP-complete problem. “Usually” because, when one is using a probabilistic approach for program synthesis, this is not the case.

The area of program synthesis started a long time ago, before computers. In 1932, famous soviet mathematician Andrey Kolmogorov already talked about algorithms with proofs that come from constructive mathematics. This is very distant from what is currently discussed as program synthesis. A particularly important system in this area, which appeared much latter, was the Kestrel Interactive Development System (KIDS). KIDS supported program synthesis from a complex program specification by means of a series of manually applied refinement steps (maybe it couldn’t be strictly called a program systhesis system) and, according to its homepage, has been used to develop many applications in such diverse areas as scheduling, combinatorial design, sorting and searching, computational geometry, pattern matching, and mathematical programming. KIDS came close to a commercial breakthrough, which is impressive.

According to Alexandre, there are three main approaches to program synthesis:

-

Synthesizers that are specialized in a particular domain. An example of such approaches is the use of the VHDL language to describe digital and mixed-signal systems. These approaches are scalable but constrained to specific kinds of systems.

-

Synthesizers that translate a particular language into SAT/SMT language. This is a general purpose approach, but it usually focuses on specific problems, such as security. According to Alexandre, the Sketch system is one of the most proeminent examples of this approach. Given specification and a code fragment, Sketch fills in the code that the programmer did not provide. An example of the kind of fragment the Sketch receives is the following:

harness void doubleSketch(int x){

int t = x + ??

assert t = x + x;

}- Synthesizers that take as input a general purpose high-level specification. This is the line of work that Alexandre and his colleagues, such as Juliano Iyoda (also from CIn-UFPE), pursue. In this case, program synthesis takes as input the specification of the program to be synthesized and an optional set of code fragments and produces as a result a program in a language that has a formal semantics. The latter part is particularly relevant because, as long as a language has formal syntax and semantics, it can be combined with this approach. They proposed an approach and a tool implementing it, named PSAtCIn, that currently combines a DSL targeting C# code, Alloy*, and a formal specification language in an Ecplise Plugin that is already capable of producing code from general-purpose specifications. Here’s a very simple example of the kind of thing one can do with PSAtCIn. Given a specification

Vars x, y

requires: x > 1 and y > 1

ensures: x' = gcd(x, y)

sketch: while * != *

*it can generate the program

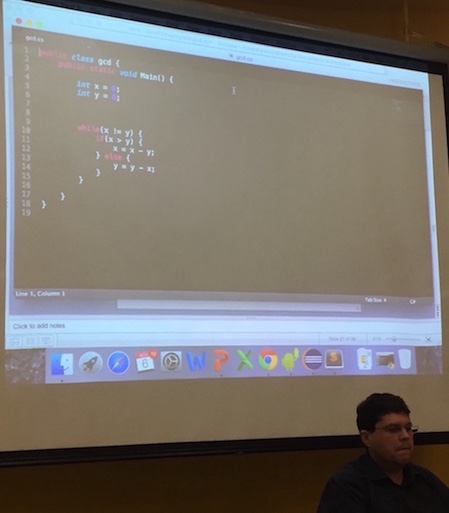

while (x != y) {

if (x > y)

x = x - y

else

y = y - xIn the specification part, gcd is a logical predicate.

Alexandre explained that this approach is currently capable of generating simple programs that include loops, e.g., it was capable of generating Euclid’s algorithm for the greatest common divisor. This is a promising result, since loops are a common stumbling point for program synthesis and verification techniques. PSAtCIn also supports sketching (similarly to Sketch) and it is extensible for other languages that have formal syntax and semantics.

Finally, Alexandre discussed some current challenges. The one that caught my attention was the recommendation of scopes for search. Since PSAtCIn uses Alloy* under the hood, it also performs bounded scope search when verifying whether a program satisfies its intended properties (pre and postconditions). In Alloy*, users must specify the bounds for the search scope. Alexandre hopes that, in the near future, PSAtCIn will be able to provide this kind of information automatically in program synthesis.